Pokrovsk: The City Russia Can’t Capture and Ukraine Can’t Lose

The Night the Bradleys Came Back

October 15, 2024. Just after 4 a.m, a lone American-made Bradley races through the skeleton of Novohrodivka, ten kilometers southeast of Pokrovsk. Its thermal sight picks out three Russian soldiers crawling between the burned-out apartment blocks. The 25 mm cannon barks twice. Two figures drop; the third disappears into a cellar. The crew from the 47th Mechanized Brigade never even slows down. They have done this every night for a month. They know the city will not fall this week, maybe not this year, because they have turned the entire approaches into a killing box no Russian battalion can cross intact.

That single Bradley ride is the whole war in miniature. Pokrovsk is still Ukrainian, and the cost of changing that fact has become astronomical.

Why Pokrovsk Is the Real Prize

Open any map of the current front and trace the roads westward. Everything narrows to one place: Pokrovsk. It is the last big rail and highway hub Ukraine still holds on the open Donetsk plain. West of the city the ground slowly climbs toward the Dnipro plateau; east of it the land is flat all the way to the Russian border. If you want to drive tanks toward central Ukraine without fighting uphill or crossing a major river, Pokrovsk is the gate.

Seventy percent of the shells, fuel, and rations feeding the Kramatorsk-Sloviansk fortress belt come through Pokrovsk station or along the E50 highway that runs beside it. When Russian jets started dropping guided bombs on the rail bridges in October 2024, delivery times doubled overnight. Lose the city completely and half the Donbas front switches to emergency rations in a fortnight.

There is another road almost no one outside the general staff talks about: the H15 that runs north-south through the city. It is the only paved route still linking Ukraine’s northern and southern groups inside Donetsk oblast. Cut it and every reinforcement convoy has to crawl along muddy tracks that disappear in the November rasputitsa.

Then there is the coal. The mines around Pokrovsk sit on the richest coking-coal seams Ukraine still controls. Eight million tons a year before the war, enough to keep the blast furnaces in Kryvyi Rih and Zaporizhzhia running. When Russian troops reached the gates of the Tsentralna mine last month, Ukrainian sappers dropped the main shaft with shaped charges rather than let Moscow fire its own artillery with Ukrainian coal.

In short, Pokrovsk is the stopper in the bottle. Pull it and most of Donetsk oblast drains away in months. Leave it in place and the front can hold into 2026 or longer. Bakhmut was about pride. Avdiivka was about momentum. Pokrovsk is about survival.

How Russia Tried and Failed (So Far)

The offensive began in earnest after Avdiivka fell in February 2024, but the real push on Pokrovsk started in May.

First came the lunge up the H20 highway from Ocheretyne, the so-called highway of death. Russian columns lost dozens of vehicles a day to Javelins and drones, yet by August they had clawed to within sixteen kilometers of the city. The price tag: roughly 1,400 men for every kilometer gained, the worst exchange ratio of the entire war.

In September Moscow switched to a southern hook, trying to envelop Pokrovsk through the mining towns of Selidovo and Ukrainsk. They took Novohrodivka street by street, but Ukrainian mines and artillery turned every advance into a massacre. By mid-October infiltrators in civilian clothes were inside the city limits, some only eight kilometers from the central square. Fog, drones, and the 47th Brigade’s Bradleys stopped them cold.

Since November the front has barely budged. Russian battalions now attack in pairs or threes, slipping forward under cover of weather. Most never make it back. Ukraine’s new FPV-interceptor drones and the first dedicated unmanned-air-defense platoons have pushed Russian drone losses above seventy percent in the sector. The pocket south of the railway is still contested, but the city center, the station, and the vital western exits remain firmly Ukrainian.

Russia has already burned through more than 100,000 casualties trying to take Pokrovsk. That is more men than the Soviet Union lost storming Berlin in 1945.

The Defenders

The units holding the line read like a roll-call of Ukraine’s best remaining formations:

- 47th Mechanized Brigade with its Bradleys and a reputation for vicious counterattacks

- 59th Motorized, rebuilt twice and still fighting as hard as ever

- 25th Airborne Brigade holding the northern shoulder around Rodynske

- 15th Kara-Dag National Guard turning mine buildings into fortresses

- 68th Jaeger in the south, who paid in blood to keep the southern pincer from closing

Western weapons matter here more than anywhere else on the front. Cluster shells from American 155 mm guns tear apart assault groups in the open. Excalibur rounds drop on command posts the moment they emit a radio signal. HIMARS still hunt Russian supply columns thirty kilometers behind the lines. But the real game-changer is the drone. Ukrainian operators now say, “We don’t need as many artillery shells any more. We just need batteries and carbon fiber.”

The Civilians Who Stayed

Before the war sixty thousand people lived in Pokrovsk. Fewer than fifteen thousand remain. The evacuation trains still run when the shelling pauses, but hundreds refuse to leave. Miners go down eight hundred meters every shift because the coal pays for the shells that keep the Russians back. A school principal named Olena continues to cook pots of borscht in the basement of a ruined kindergarten and carries them to whichever brigade is holding the next street.

Svitlana Storozhko, forty-five, still opens her little grocery at dawn. The shelves are half-empty, but soldiers know they can get cigarettes and instant coffee there. “My cats left with the neighbors,” she says, “but I stay. Someone has to feed the boys.”

Where We Are Right Now

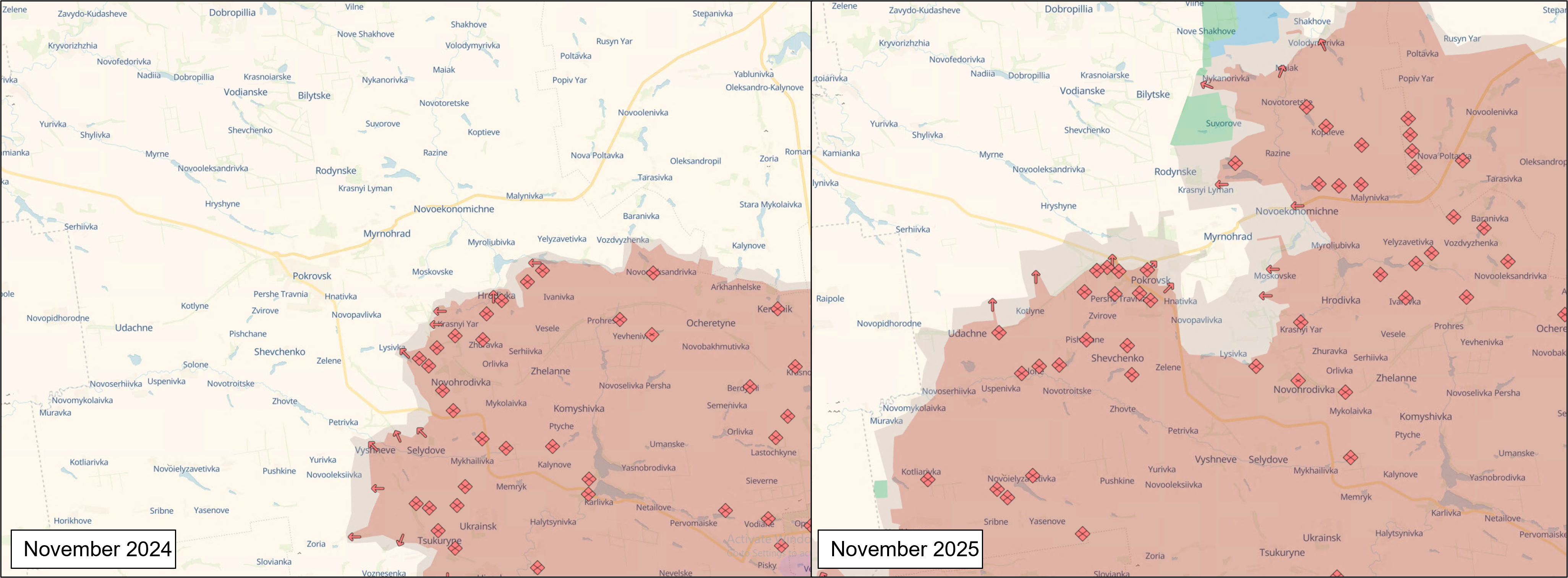

As of November 27, 2025, Russian troops control roughly the southern third of the city and most suburbs to the east and southeast. Ukrainian forces hold the railway station, the central square, and a narrow but vital corridor northwest toward Myrnohrad. The front is measured in hundreds of meters now, not kilometers. Both sides are exhausted, yet neither has the reserves for a decisive blow before spring.

Three plausible futures await:

1. Ukraine stabilizes the line through the winter, rotates fresh brigades, and launches a limited counteroffensive in April or May once longer-range missiles arrive in numbers.

2. The fighting freezes into a brutal siege that lasts another year, draining Russian manpower faster than they can recruit.

3. Russia finds one more fresh division, closes the pocket around Myrnohrad, and forces a withdrawal that shortens the front by fifty kilometers at the cost of another fifty thousand lives.

Last Thought

On clear nights you can still see the glow of Pokrovsk from twenty kilometers away, a faint orange pulse on the horizon where generators and burning buildings compete for light. The city has become a fortress that bleeds its attacker white. Whether it holds until the wider war turns, or finally falls after a winter no one wants to imagine, one thing is already certain: Pokrovsk has replaced Bakhmut and Avdiivka as the place where the Russian offensive came to die.

For now the stopper is still in the bottle.